Drinking culture runs deep in Japan, and sake is undoubtedly the country's most representative liquor

Known more commonly in Japan as nihonshu, sake comes in a range of flavor profiles and proofs and can be enjoyed hot, cold or at room temperature. Since sake is so important to the nation, a rich set of customs surround its consumption and production. It's easy to enjoy drinking sake, but choosing and ordering can be daunting for first-timers. Exploring the wide variety of this Japanese rice wine should be fun, not scary. To ease some of that anxiety, this guide breaks down the basics of the national drink.

Social drinking is common in Japanese culture

Where to drink sake?

Sake can be enjoyed anywhere in Japan. Sake is a favorite tipple everywhere from bars to high-end restaurants. Most places that serve alcohol in Japan will have some basic sake options. For enthusiasts or those looking to branch out, there are many specialty sake bars and izakaya around the country with a particularly wide stock and knowledgeable staff.

If you'd prefer to buy sake to take away, you can purchase mainstream brands at local convenience stores and supermarkets. A more complete selection is available at liquor stores, department stores and specialty sake shops.

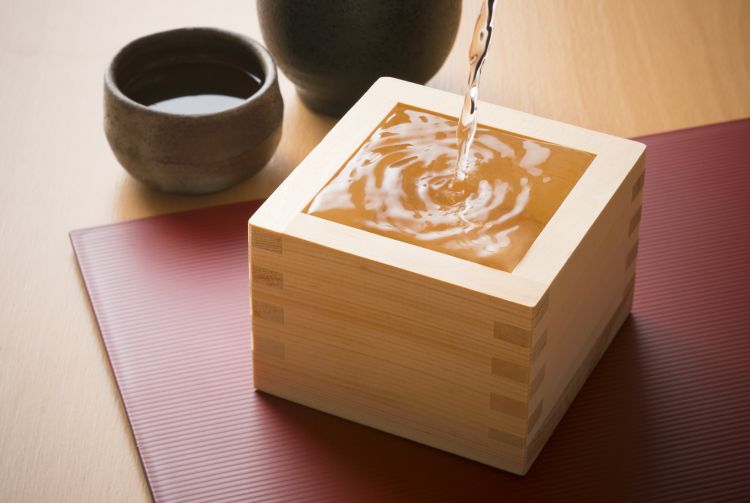

Drink from a masu for a real sake experience

How is sake served?

Sake can be served chilled, warmed or at room temperature. Some types, like ginjo, are preferred cool, while junmai is often enjoyed at room temperature or warmed. Each individual sake has its own temperature that best brings out the flavors, and personal preference is extremely important as well.

A traditional sake set consists of a serving carafe called tokkuri and smaller personal cups called ochoko. Sometimes a small glass is placed inside a box, or masu. In some places, the sake will be poured until it overflows into the masu.

Since masu were the main sake vessels in the past, most are sized to one standard serving of 180 ml, called go. At many bars and restaurants, you will be expected to order sake by number of go. Ichi-go and ni-go are one and two servings, respectively. Standard sake bottles are 720 ml, and are known as yongobin.

There are many types of sake—find your new favorite

Types of sake

There are a number of sake types, classified according to ingredients, production methods and the degree of rice polishing. Rice's outer layer is not ideal for brewing, so it is stripped in the polishing process.

Honjozo means the rice has been polished to 70 percent, meaning 30 percent of the grain has been removed. Ginjo is made from rice polished to 60% or less and fermented slowly at low temperatures. Ginjo with grains polished to 50% or less is called daiginjo.

Junmai is a type of sake made without brewing alcohol and using only rice, water, yeast and rice malt (koji, cultivated for food production and sprinkled on steamed rice to secrete enzymes). The term junmai is also sometimes used in combination with ginjo and daiginjo sake.

A lower polishing ratio means more rice is used and more time is spent polishing the rice, resulting in a higher price, but a higher rank does not necessarily mean it is a 'good sake'. Similarly, junmai is not a definitive mark of quality, as talented producers often use brewers alcohol or other additives to enhance the flavor or smoothness.

Other types of sake include namazake, unpasteurized sake; nigorizake (or simply nigori), sake filtered through a coarse cloth, resulting in a cloudy drink with a creamy mouthfeel; and shiboritate, which is released straight from the brewery without undergoing any maturation.

It is important to note that in Japanese “sake” actually refers to alcohol in general, while the rice brew specifically is called nihonshu. There are a number of other traditional Japanese liquors, including shochu—a distilled spirit—and umeshu, a sweet plum liqueur made by steeping the fruit in alcohol.

Sake goes exceptionally well with all types of food

Sake and food pairing

Sake is an extremely versatile drink and pairs quite well with food. Classic Japanese foods such as sushi, sashimi, and tempura are obvious accompaniments, but sake with cheese, oysters or vegetables can be just as delicious. Sake is significantly higher in umami than other brews so it can enhance the flavor of very rich dishes like stews, ramen, and steak.

Like wine or beer, some varieties pair better with some foods than others. When choosing the right match at a restaurant or izakaya, feel free to ask the staff to recommend the best sake for your meal.

Sake alcohol content

Most sake is around 15 percent alcohol, higher proof than most other fermented drinks like beer or wine but lower than most distilled spirits. Almost all sake is brewed to about 20 percent and watered down before bottling.

Genshu refers to sake that has not been diluted and therefore has an alcohol content of about 20 percent and a bolder flavor. On the other end, lower-alcohol sake is gaining in popularity. Of these, sparkling sake is particularly trendy. Reminiscent of sparkling wine, sparkling sake is fun and easy to drink, especially for novices.

Order sake shaken or stirred

Sake cocktails

Although many enjoy drinking sake straight, sake cocktails have become quite fashionable. Today's sake cocktails go way beyond the sake bombs from your student days. Stylish bars are mixing sophisticated drinks using the rice brew. Talented bartenders are designing new drinks that highlight, rather than hide, the complex flavors of high-grade sake. As interest in sake cocktails grows, the drinks are becoming a fixture of elegant hotel bars and the Japanese nightlife scene.

A crisp sake under a sakura cherry tree makes for a true Japanese experience

Sake and the seasons

Historically, sake could only be made in the winter because its production requires cool temperatures. Thanks to modern refrigeration and temperature control, sake can now be brewed year-round, but most higher-end producers still only brew in the winter months. During the winter, unpasteurized sake called namazake is available. As the year goes on, sake that has been matured for longer periods of time is released.

Lightly chilled sake is a favorite spring beverage, often enjoyed at hanami parties under the cherry blossoms. Cold sake makes for a refreshing summer drink at the beach, while hot sake, called atsukan, can warm you up after skiing or a rejuvenating dip in an onsen in winter.

The two rules for drinking sake: pour for your companions and have a good time

Sake-drinking etiquette

In formal situations, there is strict sake etiquette. The most important rules are never to refill your own cup and to ensure every cup on the table remains filled.

When pouring for a superior, hold the tokkuri with your right hand while touching the bottom with your left. When receiving sake from a superior, place one hand under the cup and hold the side with your other. It is acceptable for the superior to use only one hand while pouring and receiving. After receiving the sake, take at least one sip before placing it down on the table.

In casual situations, the rules are not nearly as rigid. However, it's always polite to pour for others, whether you're drinking sake, beer or tea.

Sake regional variations

Sake is produced in almost every prefecture, but some places are especially famous for their local sake, called jizake. Many regions are known for specific flavor profiles, which tend to pair particularly well with their local specialty foods. Well-known areas include the Nada area of Hyogo, which has bold, sturdy sake, and Niigata , where the taste tends to be cleaner and crisper.

With better access to ingredients, technology, and a nationwide market, some breweries have moved away from their region's standard flavors in recent years. Try sake from both traditional breweries and more forward-thinking producers to get a feel for the range available in each area.

Take a brewery tour and enjoy a taste of local sake

Sake brewery tours

With so many breweries around the country, it's easy to get a glimpse into how sake is made. Many offer tours and some are even free and include sake tasting. Get to know the process, ingredients, and equipment before trying the finished product on the spot.

There are a number of breweries open to visitors in and around major cities such as Tokyo, Kyoto, Kobe, and Hiroshima. Be sure to make reservations.